Where do the polls go from here?

One pollster is having nightmares as the industry grapples with its third-straight big miss. But how do you measure something that's getting increasingly disjointed?

Hello! Welcome to Margin of Error, a newsletter from me about the polls and the way they are covered.

If you’re new here, thanks for signing up! If you find it interesting, I’d be grateful if you would encourage others to sign up.

If someone sent this your way or you found this post through Twitter or other channels, make sure to subscribe below.

And now, the polls.

On a Saturday night, three days before Election Day, a lot of election and polling Twitter was abuzz over a new poll from J. Ann Selzer.

Selzer’s polls are considered the gold standard in the (perhaps former) swing state of Iowa. Her last poll of the 2016 race, in which she found President Donald Trump leading comfortably, is largely credited with foretelling his triumph not only in Iowa but throughout the Midwest.

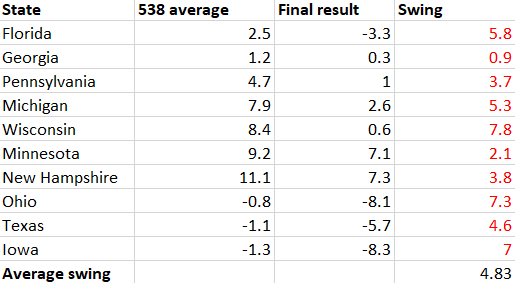

This time, her poll again found Trump leading comfortably in Iowa—by seven points. This differed from an average of polls that found tight races in the Hawkeye State. Many even showed Democrat Joe Biden ahead in the final days.

Selzer’s poll was cast aside, largely dismissed as a likely outlier. Even Ann Selzer can have an outlier, the Twitter analysis went.

Of course, Selzer did it again. Trump won Iowa by more than eight points, while Republican Senate incumbent Joni Ernst also held on by more than six points.

Over the past couple weeks, I’ve been thinking about what to say about the polls. We just had our third election in a row where there was a pretty significant polling error, the second involving the same candidate. In 2020, outside of Iowa, the outcome is different: Joe Biden is president-elect. But the polling industry, and the pundits who analyze it, are grappling again with how the data missed the mark. And yet, as I’ll argue later, it’s an increasingly complicated story to tell.

Biden’s victory is historic: He has won the Electoral College by a 306-232 tally. He is on track to win the popular vote by between three and four percentage points, and likely by between 6 and 7 million votes. Of course, even that topline number is different from polls that, according to FiveThirtyEight’s final average, put Biden up by 8.4 percentage points.

The underlying stories paint an even worse picture for polls. At least today, Democrats do not have the Senate majority polls told them to expect. And in this newsletter, I’ve written a lot about the district polls that painted a clear picture for the races for president and key House seats. As we now know, Republicans are gaining seats in the House.

So what happened, and what happens from here? I talked to a few pollsters for their thoughts, and I also have some of my own.

Donald Trump was underestimated—again

Tom Jensen, who runs the Democratic firm Public Policy Polling, is fairly torn up about what happened this cycle. He told me he has had literal nightmares about the South Carolina Senate race. This doesn’t totally make sense: His firm never polled Republican Lindsey Graham trailing. Nevertheless, PPP had found a close race that ended up being not so close.

Like a lot of other pollsters, PPP analyzed what went wrong in 2016 and made adjustments. And in the next major election cycle, 2018, it looked like it had worked. Jensen said that 2018 and smaller cycle of 2019 represented the most accurate years of polling in the firm’s 20-year existence.

He told me that 2020 reaffirmed for him that Trump is a “unique force of nature” when he’s on the ballot.

“I thought we had sort of cracked the formula for polling in the Trump Era and expected very accurate polling this year,” Jensen said, “but I guess [2018 and 2019] was just for polling in the Trump Era when Trump himself is not on the ballot.”

The most obvious reason for this, and the siren for pollsters going forward, is that a lot of Trump supporters and Republican voters not only don’t trust polls anymore, but also won’t respond to them. They have become part of the broader conspiracy, akin to the media (which, as it happens, often breathlessly reports on polls).

This problem could subside when Trump is no longer on the ballot. But some of the down-ballot races are also glaring. Graham, for instance, led in only four of the final seven polls conducted in South Carolina, and he ended up winning by double digits. In Maine, Sen. Susan Collins never led in a public poll this cycle but will end up winning comfortably.

“I think polls have just gotten absorbed into the media as something for Trump supporters to hate and distrust so they decline to participate in ways that can’t simply be fixed by weighting,” Jensen said. He said PPP may look at weighting differently if Trump—or someone with a similar following—is on the ballot again.

Of course, there are some more simple explanations for what happened, especially down-ballot. Like what happened in 2016, Jensen said a lot of undecided voters ended up breaking for Trump and GOP candidates. And as voters saw a Biden win becoming more likely, more people who have historically voted Republican felt comfortable voting Republican on the rest of their ballots, meaning that even in historically GOP suburban areas where Biden did well, he didn’t end up providing significant coattails.

Dr. Lauren Copeland, associate director of Baldwin Wallace’s Community Research Institute, is working on a version of the “shy Trump” voter theory (which she, like I, doesn’t seem to buy). She instead refers to “reluctant Trump” voters—people who don’t personally like Trump but still see their policies closer to those of the GOP.

Interestingly, Copeland told me that if you add all of the undecideds into Trump’s column in the final Great Lakes poll from Baldwin Wallace, it gets pretty close to their actual results in Ohio, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. She said they’ve had a preliminary look at the data from that October poll and found that undecided voters largely approved of Trump’s job performance and his handling of the economy.

Bernie Porn, who runs the EPIC-MRA poll in Michigan, had similar thoughts but put it more bluntly: He thinks there’s a “lie factor” among some voters when it comes to Trump—particularly those who say they planned to vote third party. If Trump or someone like him is on the ballot again, he plans to ask more probing questions to those voters.

“When Trump is not on the ballot and pollsters are testing voter opinions about more normal candidates that are not as controversial as Donald Trump, polling has been much more accurate,” he told me.

How do you measure something so disjointed?

There are big questions the polling industry will have to answer in 2022 and 2024, although the interest around polls will only intensify. (Don’t believe the “polls are obsolete” crowd.)

I may expand on this point in a future issue, but I think it’s worth mentioning even in passing. I think part of the reason polls have been missing the story is that the story itself is becoming more and more disjointed.

This was not a particularly close election. One candidate earned millions more votes than the other, while garnering the highest percentage of votes for a challenger since FDR.

And yet, even in an election in which there’s a clear outcome, it seems evident that at no time in the near future will the United States have a not-close election under its current system. Dave Wasserman of the Cook Political Report noted the divergence in Wisconsin, which was the “tipping point” state in both 2016 and 2020. The 2020 election is on track to have the biggest discrepancy between the tipping point and final popular vote margin since at least 1948.

Polls have become more than just data. They are a coverage point and a barometer, and they come together to help people tell a story.

A blend of flavors combine to shape how we perceive an election in its aftermath. In 2020, the narrative was shaped by a couple of distinct elements: Expectations for Biden were set high because of the polls, and The Narrative that those polls were way off was established early on election night by returns from Florida and, to a lesser extent, North Carolina.

How would we be covering this election if it had happened another way? If Republican legislatures hadn’t blocked Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania from counting mail ballots early? If we had known pretty quickly the final score, instead of waiting days for the next batch of ballots to trickle in? We’d know the polls were off, but it wouldn’t feel quite the same, would it?

So, the polling industry will grapple with its third big miss in three elections (and 2012 rivals 2016 and 2020!). But in a system where one candidate can lose by at least 6 million votes and still come within 25,000 or so vote switches of winning, well, that’s a hard story for even data to square.